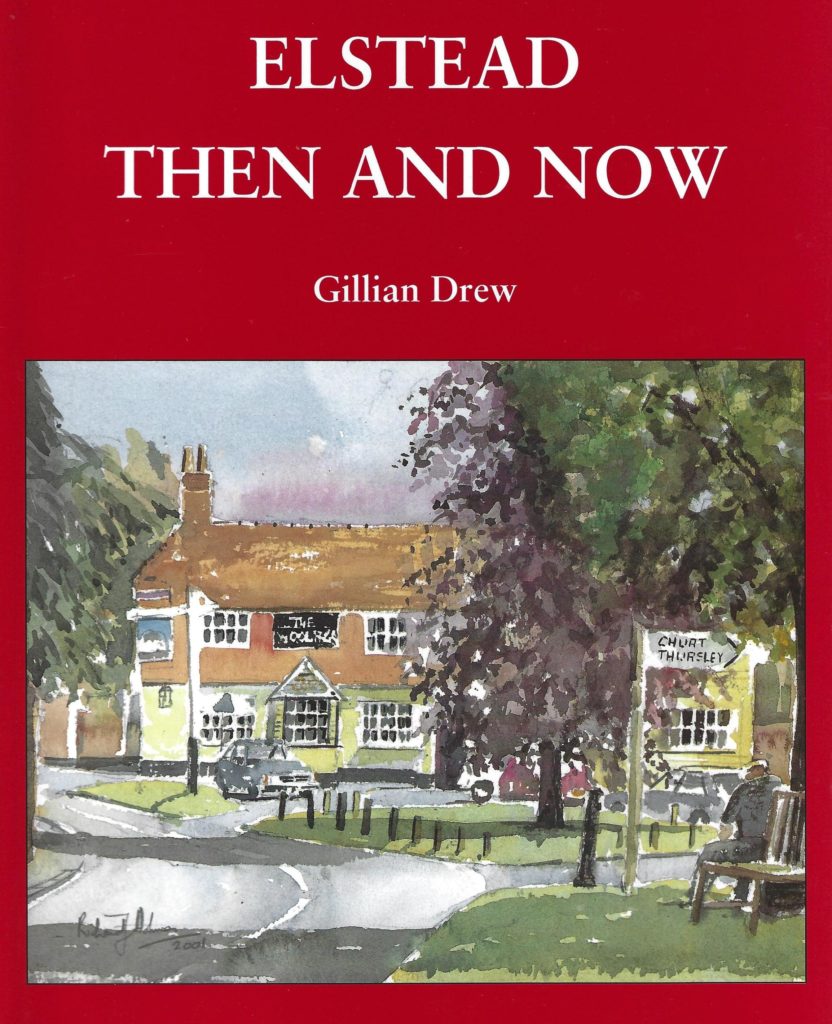

Elstead Then and Now

Adapted by Allan Collis from the book by Gillian Drew

“There is nothing so constant, or predictable, as change. This history of a nation, or a village plays a key role in shaping our future …. I believe that no Elstead household should be without a copy of this book.” Carol May

Gillian Drew lived in Elstead for over 20 years and was a librarian with a keen interest in local history and archaeology.

She was Honorary Librarian of the Surrey Archaeological Society and took part in a number of local excavations at Wanborough, Guildford, Dunsfold and Cranleigh.

This adaptation of Gillian’s book includes extracts from all chapters, however much more information can be found in the book itself, which unfortunately is no longer in print. However used copies can sometimes be found online, and in the homes of village residents.

Contents

click on chapter headings to read longer extracts from the book

“Helstede”, “Elestede”, “Elestede”, “Elsted” and “Elstead” – the place has been called all these things, according to the changing fashion of the times, or, more likely, the eccentric spelling of medieval scribes, parish clerks and their like.

It is suggested that it comes from the old English “ellen-stede”, “place of the elder trees” although no forms with the “n” are known, and the earliest mention of the name at all is in the foundation charter of Waverley Abbey in 1128.

The first mention of Elstead by name comes in 1128 when the Bishop of Winchester, William Giffard, bestowed on the Cistercian monks from the Abbey of Aumone in Normandy, all the lands at Waverley with meadow and pasture, together with two acres of meadow at “Helestede”, together with pannage, or grazing for their swine, and liberty to cut wood for fuel in his woods at Farnham.

The new Stuart dynasty was very much an unknown factor, and people awaited the new era and the new century. Bridges were causing some trouble in Elstead. There was also evidence, however, of growing organisation of local government to deal with local needs. A rent of 2/- per year was set aside for the repair of Somerset Bridge, over the Wey, on the road from Elstead to Shackleford. We begin to see a few more people coming onto the stage.

The village at this time would have been composed of small field strips either of grass or ploughland, and a ribbon development of houses along Thursley Road as far as the Church, Milford Road and Farnham Road, with no connection between the three. As late as 1933 the field below the bridge, opposite the Mill, was still divided into seven strips, with the owners each cutting their own hay each year. This area must have escaped somehow when the Enclosure Act, which basically put an end to the medieval system of strip farming, was completed in Elstead in 1851.

In 1801 there were 79 inhabited houses occupied by 103 families. There were 225 males and 241 females. 274 were chiefly employed in agriculture and 45 in trade. The total population was 466. There was a steady increase in population up to the middle of the century as is shown by the ten-yearly census returns. In 1811, it was 521, in 1821 – 608, in 1831 – 711, in 1841 – 743 and in 1851 – 841. There was a slight falling away after this date, perhaps there was a drift to the towns in search of work. In 1871 the population was 756, in 1881 in was 679. There was then a steady rise to 775 in 1891, to 904 in 1901, to 1036 in 1911, to 1029 in 1921 and to 1291 in 1931.

There was a pottery at Charles Hill until 1914. The clay was probably obtained from Moor Park, and the wood for firing the kilns was collected locally. The works were owned by one Absalom Harris. He later moved to Wrecclesham, where his son still had a pottery in 1937, and which is still operating.

It has been mentioned that there was a school on the corner of the turning leading down to Weyburn; this was a Dame School, and seems to date from around 1837. The next school, The British School, was built by the Mill owner primarily for workers children. It charged 2d a week school fees and sometimes this sum would be docked from the parents wages.

The 19th Century, as it gathered pace, and the speed of industrial development increased, provided many examples of individual self improvement and there was admiration of the ethic of self help as advocated by the Rev. Samuel Smiles and others. In 1849, Elstead’s National School was opened by pioneering Church Men to serve the village as a voluntary Church of England School, to give the children elementary instruction in the 3-R’s.

There were significant changes in the religious life of the village during the 19th century. There has already been mention made of the change of status at St. James. By 1811, Frensham, Seale and Elstead had been separated from Farnham for civil purposes, but they were still linked for ecclesiastical. The tithes of Farnham and its dependent chapelries were habitually let out by the Archdeacons for a term of 3 lives, with fines on renewal, and the right of nomination of a Curate. In 1840, Bishop Sumner introduced a Bill in the Lords to anticipate the calling in of the leases, and to restore the tithe money to the parishes, but it was opposed and withdrawn.

Although Elstead has seen a tremendous influx of population with much new building, Elstead people have always been firmly rooted in their native heath, given to moving around the village perhaps, in their progression through life, from a big house to a small one, but never leaving the village entirely. We have already remarked on the continuity of families in the area, and this has continued to be the case all through the changes of two world wars, and countless other upheavals. Even today, a significant proportion of the population have parents and even grandparents from the village and, whether as a result of this or not, it is hard to say, community life flourishes.

I would like to record my sincere thanks to Mrs Carol May, without whose help this book would never have seen the light of day, also Mr Clive Warren, for his help and information, and permission to use his picture collection. Mrs Prue Bardelli and Mrs May Deaville started me on this road over fifteen years ago, and I would like to repeat my thanks to them and all of those who then and since have supplied me with information. I hope they will pardon my deficiencies and enjoy reading about “Elstead Then and Now”. My thanks also go to Mr Alan Collis who labored to transfer my text to the Internet.